Over the past few years, blue carbon has gone from a niche subject to one of the most popular topics in various circles, including aquaculture. It’s clear that there is a lot to be excited about when it comes to blue carbon, but why is it drawing so much attention?

Blue carbon refers to the carbon that is captured and stored in marine and coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, seagrass meadows and salt marshes. These ecosystems act as natural “carbon sinks,” that store up to 10 times more carbon per unit area than their land-based counterparts. This superpower means that blue carbon is gaining attention in the race to mitigate the effects of climate change. According to the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, as much as a fifth of the emissions cuts we need to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5C will need to come from the ocean. The panel also says that protecting and restoring seagrass, mangroves and salt marsh ecosystems could help absorb the equivalent of as much as 1.4bn tons of emissions a year by 2050.

But that’s not all — ecosystems like seagrass meadows and salt marshes provide other benefits such as offering protection against extreme weather events and supporting biodiversity. Seagrass can stabilise sediment beneath its roots, limiting erosion, while salt marshes filter pollutants and reduce flooding by absorbing excess water. Now, they are also urgent new areas of conservation.

Blue carbon is also gaining traction with aquaculture, in particular seaweed farming. The benefits of farming seaweed are already clear. Seaweed doesn’t need feed or additional attention as the plant grows naturally, creating safe, healthy nursery grounds for young fish and crustaceans. Increasing seaweed farming may also open the door to a more efficient form of renewable energy — biomass — while seaweed’s ability to break down environmental pollutants and improve water quality makes its development a significant priority for aquaculture.

But like seagrass meadows, mangroves and salt marshes, seaweed can also sequester carbon. In fact, there are already seaweed farming projects with the goal of capturing carbon from the atmosphere, for example in Norway where technology and farming methods are being developed to capture CO2 through seaweed cultivation. With seaweed farming facing challenges such as the limited scope for expansion due to the availability of suitable areas and competition for these areas, rearing systems that can cope with rough conditions offshore, and increasing market demand for seaweed products, some say that providing farms with economic incentives associated with proof of climate change mitigation may be instrumental in improving the income of seaweed farmers and supporting increased seaweed production into the future.

I’ve found it very exciting to see how aquaculture companies are realising the appeal of blue carbon and want to be a part of something that delivers social, economic and biodiversity benefits. In November 2022, kelp restoration and sea urchin aquaculture firm Urchinomics obtained the world’s first voluntary blue carbon credit for kelp bed restoration. By paying divers to remove sea urchins from kelp beds that have been overgrazed by sea urchins, Urchinomics helps the kelp beds to recover while turning the sea urchins into seafood through aquaculture (the sea urchins are grown on indoor raceways and fed pellets made out of kelp-stem byproducts). The Japan Blue Economy Association (JBE), a state-appointed research institute in Japan that establishes blue carbon credit standards for the country, validated Urchinomics’s science and certified the voluntary blue carbon credit. In a press release, Brian Tsuyoshi Takeda, the CEO and Founder of Urchinomics, expressed his hope that “other kelp-supporting countries will look to the Japanese precedent and accelerate their adoption of kelp as a blue carbon opportunity.” He also said “while it is called blue carbon, make no mistake that the true value in restoring kelp forests is about biodiversity. Kelp forests are one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on our planet, and meaningful carbon sequestration only happens when biodiversity is championed at the same time.”

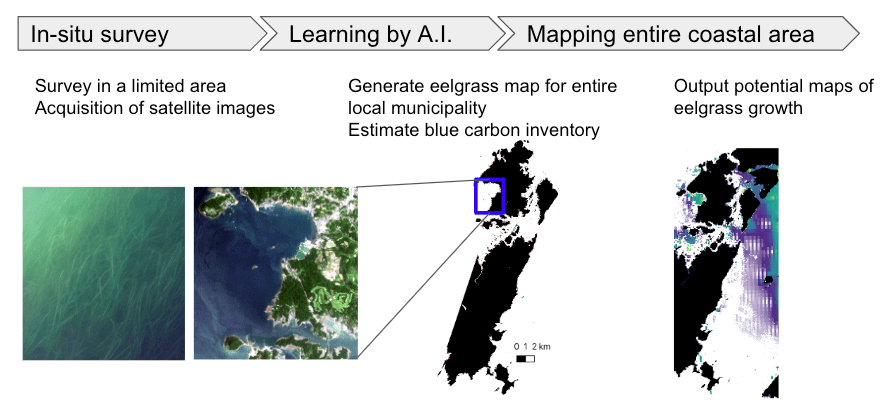

A couple of months ago, I heard about Japan/Singapore firm Umitron’s new project to identify blue carbon sinks, and am looking forward to delving into this subject a bit more over the summer. Umitron says that although blue carbon has immense potential, identifying and mapping ecosystems like seagrass meadows, salt marshes and mangroves is a big challenge, involving labour-intensive field surveys that can be time-consuming and costly. Recognising this issue, the Umitron team are using their AI technology and satellite remote sensing capabilities to identify, map and analyse coastal areas, focusing on seagrass beds, mangroves, seaweed and more. The team starts with a limited survey of a particular area, collecting data on the target species, before using AI algorithms to understand growth conditions and train the AI model to identify habitats that would be ideal for the accumulation of blue carbon. The team then leverages satellite images to analyse coastal regions, estimate areas where particular species grow, and identifies existing and potential blue carbon sinks in the process. The project can also estimate the amount of blue carbon that is accumulated in different areas. This can provide valuable insight into the potential of carbon sequestration in a particular site and potentially pick up suitable areas for seaweed farming.

There is undoubtedly a strong case for blue carbon projects, considering just how much carbon is removed by seagrass meadows, salt marshes and mangroves. However, there are some challenges to consider. For example, the ability of these ecosystems to continue storing excess carbon from the atmosphere could depend on how climate change will impact them. These impacts could be complex, and vary from one marine ecosystem to another, or even from one species to another within the same ecosystem. Blue carbon projects are also specific to the environments that they operate in, which could make it harder for them to be scaled or implemented globally, while restoring ecosystems like salt marshes, mangroves or seagrass meadows for the purpose of carbon sequestration is a major task. Another issue is estimating how much carbon particular ecosystems can soak up, while the science behind blue carbon is still developing, despite being an important part of the complex jigsaw to fight climate change. It’s possible that the focus and hype surrounding blue carbon could result in high expectations and the risk of very different or unexpected outcomes if a project is scaled further or implemented in an environment where it might not be suitable.

In fact, researchers from the University of East Anglia (UEA), the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the OACIS initiative of the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation have challenged the view that restoring ecosystems such as seagrass meadows and salt marshes can remove large amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere.

In their study, they point to the vulnerability to future climate change and the high variability in carbon storage rates. They also explain that extra habitat will be required for extra carbon removal, but such habitats have already been built on for coastal settlement, tourism and port development. They also say that CO2 removal through coastal blue carbon restoration has questionable cost-effectiveness when considered only as a climate mitigation action. Comprehensive, long-term monitoring will be required to verify that the intended climate benefits are being achieved. On the whole, however, the study does stress the need for blue carbon habitats to be protected and, where possible, restored, given their benefits for climate adaptation, coastal protection, food provision and biodiversity conservation.

Blue carbon projects are not going to go away, and yet it’s clear that more work needs to be done. These projects will have to be flexible and adaptable to the context in which they operate, while perhaps we need to recognise that blue carbon is just one of many tools, not the full answer that we are looking for. Although blue carbon projects provide significant benefits, they aren’t suitable for every environment and will need to be done in the right one. But if we get it right, we can unlock their potential, and this can lead to more sustainable livelihoods and the preservation of important coastal habitats alongside the carbon benefits.

The increased focus on blue carbon has meant that we are also more aware of the need for investment in the conservation and restoration of marine ecosystems like seagrass meadows, salt marshes, mangroves and seaweed beds, and that’s a huge step forward. As we know, the importance of ecosystems like these extends beyond just carbon storage. While there are still challenges when it comes to blue carbon, and no doubt other setbacks to come, conserving and restoring blue carbon ecosystems is a gold mine in terms of environmental, economical and social benefits.