Within the ocean lies immense reservoirs of carbon, surpassing those in the atmosphere or on land. By actively capturing and incorporating carbon through various natural mechanisms, the ocean locks in significant portions that would otherwise circulate within the Earth’s systems. This crucial role mitigates climate change by reducing the amount of carbon that ends up in the atmosphere.

Japan’s efforts with blue carbon — carbon dioxide sequestered by ecosystems such as seagrass, seaweed and tidal flats — have been in the spotlight for some time and continue to gain momentum. By 2050, the country intends to develop innovative strategies to reduce atmospheric CO2, revitalise ocean habitats and local economies, and allow sponsors to offset carbon emissions by providing financial support through blue carbon trading schemes.

Last year and this year, together with consultancy firm Hatch Innovation Services and Idemitsu Americas Holding Corporation, I took a deep dive into Japan’s blue carbon utilisation efforts, including blue carbon projects across the country, the advantages and challenges of such projects, how carbon dioxide sequestration is calculated, the role and significance of fisheries cooperatives, the Japan Blue Economy Association (JBE) and the carbon credits it generates through its J-Blue Credit scheme. Although several challenges remain, blue carbon appears to hold some promise in efforts to address climate change and promote sustainability.

Since my work with Hatch and Idemitsu, blue carbon initiatives in Japan and beyond have continued to draw attention. As their work in the blue carbon sphere continues, in May 2024 Hatch and Idemitsu announced the launch of the Blue Carbon Innovation Studio – an initiative for companies that have technology and innovations that can sequester carbon through ocean and coastal ecosystems.

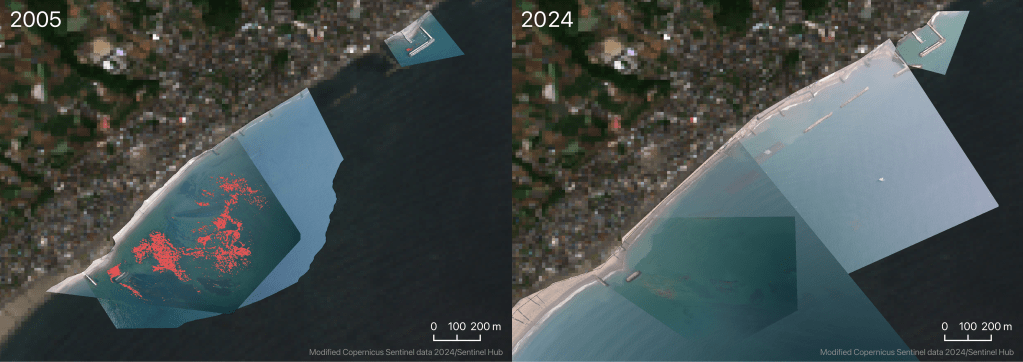

It’s also encouraging to see companies paying attention to blue carbon projects, not just because of their environmental benefits but also for their co-benefits such as protecting coastlines, supporting fisheries, local communities, hospitality and tourism, and providing cultural value. In Japan, these co-benefits have been, and still are, greatly emphasised. In the meantime, tech firms are also getting in on the action. Last month, Japanese/Singapore firm Umitron shared with me some more information on its work in Miura Peninsula near Tokyo. Making use of its AI expertise, the company was part of efforts to map eelgrass beds in the Miura area. Using aerial photographs from 2005 and 2024, advanced AI image analysis technology was employed to detect and map eelgrass beds in Miura with high precision. The result was an eelgrass map that was generated based on areas with clearly visible and identifiable eelgrass beds from selected areas. This type of work makes it possible to rapidly and accurately assess the current state of critically important habitats like eelgrass.

Umitron is no stranger to satellite imagery and ocean models. It has used both before to create seaweed bed maps in southern Japan, using in-situ verification methods to ensure the accuracy of the AI-generated results.

However, there is still much work to do to maximise blue carbon’s potential. As I discovered through my work with Hatch and Idemitsu, the blue carbon market and sector are very much in their infancy, not just in Japan but also around the world. Collaboration between scientists, technologists, investors, industry and policymakers will be key to establishing innovative solutions.

Another challenge is climate change. Although blue carbon ecosystems can be quite resilient, they are often on the front lines of impacts such as sea level rise, increasingly frequent storms and marine heat waves, and these show no sign of abating. Meanwhile, isoyake, the large-scale disappearance of seaweed beds along Japan’s coastal areas, is also causing concern. Among the various reasons that have been pointed out for its occurrence, one significant one is the effects of feeding damage from sea urchins and herbivorous fish. Amidst these issues, are blue carbon projects an opportunity to help reverse the negative effects, restore lost ecosystems and harness their potential as carbon sequestration hotspots?

Possibly, but high implementation and monitoring costs can limit the number of projects, while the cost of the credits that buyers purchase do not necessarily cover the costs required for monitoring and restoration. Another significant obstacle is the difficulty in quantifying and calculating the carbon that some ecosystems sequester. Could there be scope for something else, such as seaweed farming, to occur as part of a project? What might be a scalable solution? Blue carbon projects can be challenging to scale up, given the transboundary nature of some ecosystems or overlapping land tenure rights. These ecosystems need to be viewed in different ways so the focus is not solely on how much carbon they can store. Technology can also have its drawbacks. Umitron explained that it can be difficult to detect submerged eelgrass beds below the surface of the water, and results can be an underestimation of an actual ecosystem. Despite this, however, the resulting maps from the Miura project have clearly illustrated a significant decline in eelgrass beds from 2005 to 2024.

In Japan’s case, restoration efforts must also be able to withstand potential future scenarios like earthquakes, tsunamis or typhoons. The local engagement and support that blue carbon initiatives have received so far are extremely important, because coastal communities often directly interact with blue carbon ecosystems for livelihoods, fishing, tourism and protection from natural disasters. Engaging these communities ensures sustainable conservation efforts, and luckily Japan’s blue carbon projects have a significant focus on this, by tapping into the knowledge and expertise of local fishermen, or involving communities and younger generations by seagrass planting or educational workshops. This is a great example of integrating carbon sequestration goals with other conservation and management objectives such as sustainable fisheries or coastal resilience.

Indeed, as Umitron told me, “local community involvement at the grassroots level with residents and organisations will be essential in driving effective blue carbon conservation efforts.”

The rewards of blue carbon could extend well beyond any one industry, helping to slow climate change and avert its worst consequences. They also promise an exciting new chapter in Japan’s strong relationship with its surrounding seas.