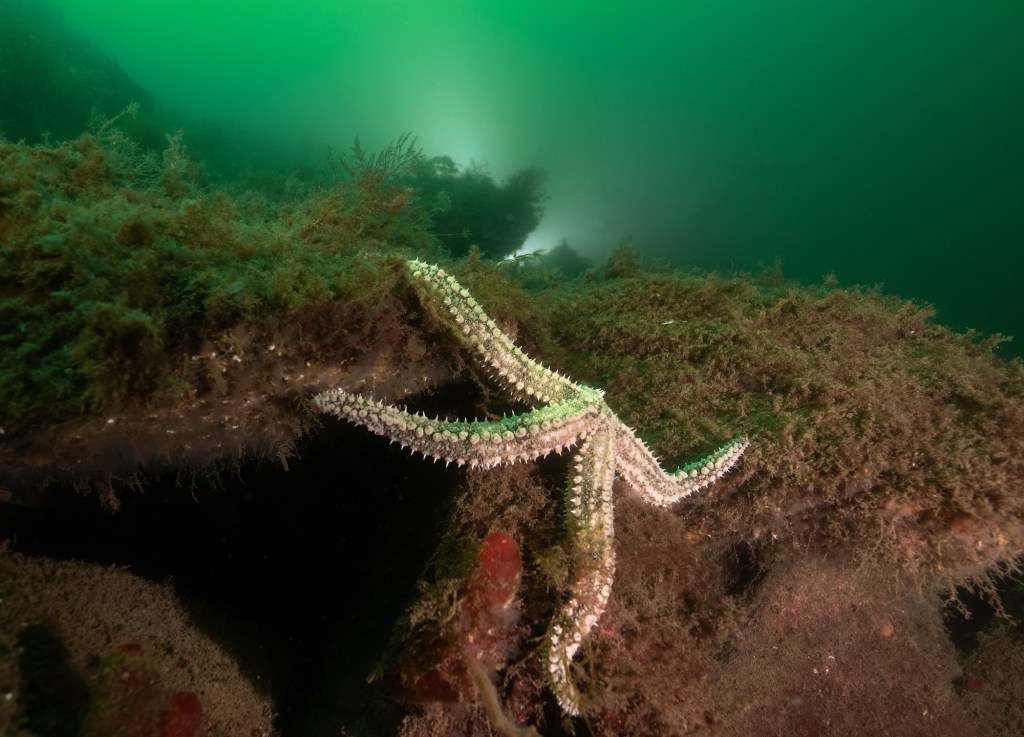

Earlier this month, Mowi Scotland sent me a press release and some underwater photographs taken around its salmon farm at Loch Hourn. The images were taken by a dive team from Tritonia Scientific, an independent marine survey consultancy, after Loch Hourn was the subject of a recent environmental pollution report. They show how a huge range of species is thriving, with the seabed and mooring lines teeming with life from feather stars, kelp and sponges to squirts, jellyfish, wrasse and anemones.

The press release also included some comments from Stephen MacIntyre, Head of Environment at Mowi Scotland.

“Protecting our marine environment is at the heart of everything we do,” he said. “That’s why we commissioned an independent environmental survey of the seabed and waters around our salmon farm at Loch Hourn.”

“There are a lot of misconceptions around the environmental effects of fish farming, with rush to judge and apportion cause and effect,” he continued.” In response, it’s important we acknowledge such concerns but that we also investigate, monitor and transparently present observational field data to inform more reasoned opinions. At Mowi, we are committed to responsible and sustainable operations that ensure we meet our environmental standards and thresholds. We take any concerns that we are not operating to those standards seriously. When claims were made that our farm was harming the loch, we investigated. The results are clear: salmon farming in Loch Hourn is not damaging the marine ecosystem. In fact, it’s coexisting with it.”

“The photos definitely speak for themselves. This is what responsible fish farming looks like in a well-managed environment,” MacIntyre concluded.

Fish farming is a huge food production sector that contributes to the global economy, food safety and more specifically to rural development in coastal areas where employment opportunities are often limited, e.g. islands. However, with the global push towards sustainable development and blue growth, understanding and addressing the environmental impacts of fish farming is crucial. We often hear about its negative impacts, such as water pollution from the release and accumulation of waste, the transmission of disease, escapes and the use of antibiotics and chemicals. However, when done wisely, fish farming can be part of the solution, slowing or stopping the negative impacts and helping to restore ecosystems. As Mowi Scotland’s photos show, Atlantic salmon and the wider ecosystem in Loch Hourn can flourish side by side. This is just one of many examples of how offshore fish farms can co-exist alongside, and significantly benefit, marine life.

In the Mediterranean, finfish, in particular bluefin tuna farming, is one of the most common types of aquaculture. There, one study confirms the benefits of fish farms to the surrounding marine environment. Researchers at the Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries in Split, Croatia, say that wild fish aggregations near caged farms can persist year-round due to abundant food supplies. Fish are also attracted by additional structures that provide protection and numerous favourable habitats for juveniles. According to the researchers, this impact of aquaculture on marine life can be considered positive as it enables adults to be in good condition for future spawning, while artificial nursery grounds can be provided for juveniles that inhabit areas within aquaculture installations. Considering the fact that each fish farm represents additional nutrient/energy input into the surrounding ecosystem, the role of wild marine biota aggregated around farming sites is also important in preventing local degradation of the environment.

The study concludes by saying that well-balanced, properly managed marine aquaculture operations should not significantly alter the surrounding environment. It adds that identifying potentially suitable areas for fish farming should take into account the ecological, technological, economic and socio-cultural impacts of different locations to avoid any environmental pressures.

Researchers at the University of Michigan agree that carefully managed farms make it possible to farm more food from the sea while reducing any negative impacts on biodiversity. In order to predict the impact of increased seafood production, the researchers built a model to determine the effect of offshore farms on over 20,000 species of marine fauna, and how this could change by 2050 depending on what was farmed and where. They found that building farms in the most eco-friendly areas led to promising results for both fish and shellfish. Bivalve production could increase by 2.36-fold and finfish production by 1.82-fold compared to current production, while global farming impacts would decrease by up to 30.5 percent under the best-case scenario. The researchers also point to the importance of strategic planning when installing farms and working with experts from various fields who can assess a wide range of considerations.

Shellfish aquaculture is also deemed as having positive effects on the marine environment. Not only is it able to improve water quality by assimilating nutrients from surrounding waters, but it also provides habitats to juvenile fish in areas where oyster reefs, algae ecosystems or seagrass beds have degraded. Compared to fish, shellfish typically do not require any chemical treatments such as high amounts of antibiotics. One of my favourite examples of shellfish farming improving ocean health and biodiversity is mussels. These can be grown on ropes suspended in the water, resulting in little to no habitat disruption. Because they feed naturally by filtering algae and other plankton, they also play a key role in improving the quality of the surrounding water. In addition, by creating biogenic reefs on the seafloor from clumps and shells, it’s possible to attract a range of species from demersal fish to macroalgae and mobile benthic invertebrates. Studies in New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf also show that mussel farms not only support marine biodiversity but also increase wild fish populations. Research at the University of Auckland has revealed that marine species near mussel farms display greater diversity and abundance. Fish also appear to consume more nutritious diets near farm sites, suggesting that mussel farms can bolster biodiversity and fisheries productivity when implemented in the right locations.

These examples represent a paradigm shift in farming at sea, transforming it from a potential environmental threat into a tool for increased biodiversity and restoration. As aquaculture expands and we look to the future of sustainable, responsible seafood production, fish and shellfish farming stand out as promising solutions, acting as biodiversity hotspots, nurseries and places of refuge for a variety of species. With continued research and development, they have the potential to make a difference by playing key parts in the production of sustainable protein and contributing to marine conservation objectives. This, in turn, is likely to greatly boost social and economic benefits in certain areas. Hopefully, these efforts will continue and we reach a future where more fish and shellfish farms help restore and protect marine biodiversity while feeding the world.