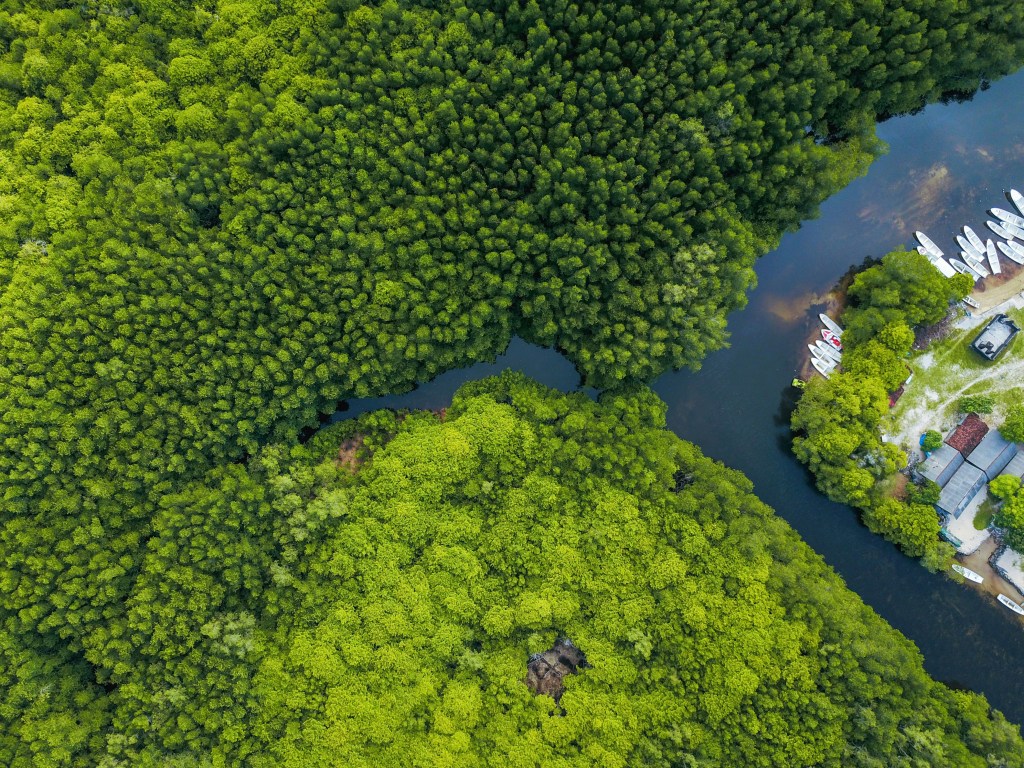

Mangrove forests are one of the world’s most productive ecosystems. They are huge biodiversity hotspots, providing habitats for various species and supporting coastal communities by protecting them from storm surges, erosion and tropical storms. They are also a vast carbon sink that can store up to five times more carbon per acre compared to rainforests.

However, mangroves have been declining significantly over the years. By the end of the 1990s, global mangrove cover was estimated to have decreased by 35%. This was followed by a further 2.1% (3,363km2) decline between 2000 and 2016. The cause is primarily due to human activity, such as forest clearing and exploitation for timber production and raw materials, rapid coastal population growth, urban expansion and conversion to agriculture and aquaculture. In fact, growing aquaculture development has resulted in swaths of mangroves being converted into shrimp ponds to meet the rising global demand for farmed shrimp.

Shrimp farms have long been accused of widespread mangrove destruction, but is this claim a fair one? This month, I took a deep dive into shrimp farming and mangrove deforestation and discovered some good news — that transformation is possible. Many countries, NGOs and private firms are actively looking for better ways to farm shrimp while safeguarding and replanting mangroves. I discovered a range of initiatives to establish tools and frameworks for environmentally responsible shrimp production and the farming of other species. The aim of these initiatives is to plant and restore mangroves through responsible farming, allowing mangrove ecosystems to flourish and provide a host of benefits.

Ecuador and Indonesia are two countries that have experienced rapid mangrove loss over the years. According to the National Coordinating Corporation for the Defence of the Mangrove Ecosystem of Ecuador, more than 70% of mangroves have been destroyed to make way for shrimp ponds. Meanwhile in Indonesia, 800,000 ha have been converted mainly into shrimp ponds over the past 30 years.

However, shrimp farming in both countries plays a prominent role in global shrimp production and exports. It is also key to supporting small farmers, and this is where Conservation International comes in. This US NPO has developed an approach to farming shrimp that can help boost yields while restoring mangroves. The approach is to take half of a shrimp farm and restore it as a mangrove forest, while helping farmers increase their output on the rest. With pilot programmes in Ecuador and Indonesia, financing and technical expertise are provided to help farmers produce more shrimp, increase profits and restore mangroves. A loan fund is also being set up so that farmers can transition to more efficient production systems, while AI-based tools help to identify optimal sites for mangrove restoration.

Shrimp farming in Indonesia, while economically significant, faces several issues and challenges that have emerged as a result of its rapid development. These include disease outbreaks, massive shrimp mortality and economic losses, and water quality degradation due to the accumulation of organic matter and other pollutants in pond water and surrounding areas. In light of this, researchers are studying a mangrove-friendly shrimp farming model called silvo-fishery, which brings shrimp farming and mangrove restoration together in a low-intensity manner. The idea is to reduce environmental impacts, preserve biodiversity, and enhance carbon sequestration. According to Esti Handayani Hardi, professor at the Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences at Mulawarman University, the practice promotes a more responsible and productive system by enhancing the natural ecosystem and improving livelihoods. She says that it offers a “win-win scenario” for more effective and sustainable mangrove rehabilitation and shrimp farming.

India, too, has been accused of mangrove destruction through its expansion of shrimp farming, especially along the east coast. But the country is dedicating extensive research, money and time into finding better ways to farm shrimp while increasing mangrove replanting efforts. The Swaminathan Foundation is a research institution in Chennai with a focus on sustainable rural development. Since 1993, it’s been working in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Odisha on the east coast, where the majority of India’s shrimp farms are concentrated, and where shrimp farms and mangroves have long competed for scarce land along coastal creeks and riversides. Meanwhile, under a new initiative in the Sundarbans called Sustainable Aquaculture in Mangrove Ecosystem (SAIME), farmers are rearing black tiger shrimp. The aim of the project is to establish a model to demonstrate biodiversity-friendly aquaculture that will build a resilient ecosystem, and identify the extent to which blue carbon emissions associated with brackish water aquaculture could be reduced by integrating mangroves into shrimp farms.

It was also encouraging to hear that other types of aquaculture are doing their part, too. Back in May, I chatted to Megan Sorby, Co-Founder and CEO of Pine Island Redfish, a redfish farm in Florida that’s created a sustainable, circular food system with fish waste. The farm’s recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) produces redfish and repurposes fish waste to cultivate red mangroves and nutrient-rich plants, such as sea purslane and barilla. After discovering that the nutrient profile of the waste from their farm is ideal for growing mangroves, Sorby and her team joined forces with an environmental apparel company to do their part. They collect mangrove seeds, which are nurtured in Pine Island Redfish’s nursery spaces, and transplant them along the west coast of Florida.

“We can monitor and manage the waste nutrients that go into the mangroves very effectively, in other words fine-tune the waste to ensure that the mangroves grow in the most efficient way,” Sorby told me. “It’s very powerful to be able to say that we are using waste from farming redfish to grow plants that act as a nursery for juvenile redfish in the wild.”

These initiatives prove that systemic transformation is possible, and it’s great to see positive trends that could act as examples for other species and regions that are facing similar challenges. Through efforts to protect ecosystems like mangroves, people in coastal regions can safeguard their natural resources and livelihoods, while such efforts also contribute to other areas like emissions reductions and blue carbon. Supporting these types of initiative is imperative for creating long-term, responsible solutions that contribute to even better farming and environmental conservation.