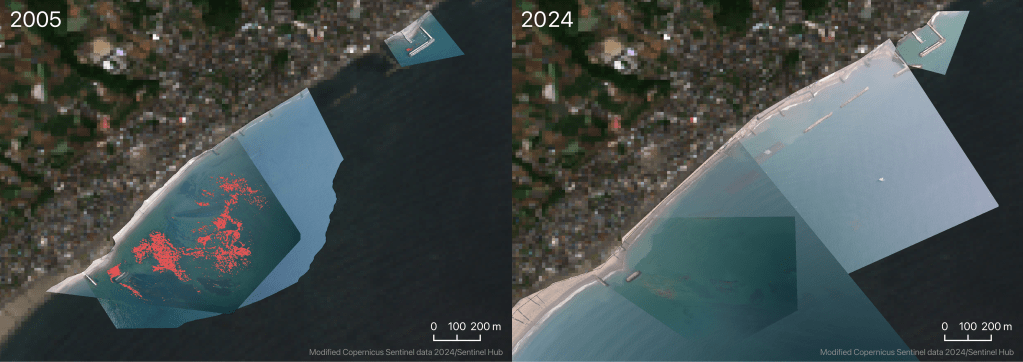

Fourteen years ago, on March 11, 2011, at 2:46pm local time, an M9.0 earthquake occurred off Tohoku, northeast Japan, on the island of Honshu. It was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in the country.

The epicenter was 80 miles (130km) east of Sendai and 231 miles (373km) northeast of Tokyo. Ground shaking lasted for over five minutes in many areas, including Tokyo, while the quake generated a devastating tsunami. In addition to thousands of destroyed homes, businesses, roads and railways, the tsunami caused the meltdown of three nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. This released radioactive materials into the environment and forced thousands of people to evacuate their homes and businesses.

The damage to aquaculture was severe. Debris was deposited into subtidal zones, crude oil and toxic chemicals were released into the ocean and seaweed forests and tidelands were obliterated. Vessels, aquaculture-related infrastructure such as processing facilities, ice plants and refrigeration, harvesting grounds as well as equipment including farming structures and products were swept away or destroyed. Certain sectors of aquaculture, such as oyster farming in Miyagi prefecture, saw a decline in oyster sales, with seedlings ready for cultivation disappearing, and a huge decline in broodstock stopping all spawning and larval rearing operations. Seawalls and breakwaters were also destroyed, leaving aquaculture areas exposed and vulnerable to storms and further tsunamis, while hatcheries that reared abalone, sea urchin and flatfish for restocking purposes were badly damaged, in some cases

resulting in an end to restocking programmes.

The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is a significant problem for Tohoku’s aquaculture today. Some of the biggest negative impacts facing the sector are an increased fear over food safety, seawater contamination and possible long-term radiation threats to food production. But things don’t end there. In 2022, the Japanese government approved a plan to release treated water from the nuclear power plant into the sea, as part of work to decommission the plant. This has faced criticism from local fishing groups fearing reputational damage and threats to their livelihoods, while neighbouring countries have expressed scepticism over the safety of the plan. As of October 2024, Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), which owned the nuclear power plant, has released threated water into the ocean five times.

Hope amidst recovery

However, amidst the effects of the disaster, there have been encouraging examples of aquaculture recovery, one of which is oyster farming in Shizugawa Bay in Minamisanriku Town, northern Miyagi Prefecture, where oysters have been farmed since the late 1960s.

Despite the difficult position that oyster farmers were in, they were determined to look beyond the destruction. Helped by the fact that the sea floor was in a better condition than anticipated, the farmers saw a chance to rebuild, and embarked on various efforts to promote environmentally sustainable and responsible practices. They decided to scale down the amount of oyster rafts from over 1,000 before the disaster to 300. The idea behind this was to reduce the scale of farming activities and create a system that would allow oysters to be harvested in just one year, to break away from overcrowding and incorporate a more environmentally-friendly type of farming.

The farmers also looked at the space between each raft, and decided on approximately 40 meters. These efforts resulted in significantly increased productivity, allowed farmers to maintain an income and lowered the risks associated with weather events.

“For example, the wind blows the rafts around, but since there is plenty of space now, boats can navigate between them safely even in the wind,” said Kiyohiro Goto of Minamisanriku town’s oyster production subcommittee. “In the past, if a raft was damaged in a typhoon or storm, it would break loose and hit the next raft, causing the damage to spread. But now there is plenty of space. Most importantly, however, the quality of our oysters has improved. They are spread out evenly from one edge of the rafts to the other, and reached 20 grams in 4 months, 56 grams in a year. We can now produce large, fine-tasting oysters.”

Resilience – a key trait

This effort is a great example of the power of incorporating sustainable farming practices and the resilience of local people amidst destruction. As my research paper on aquaculture recovery from this disaster gets underway, I’ve been struck during my reading by how often the word resilience is mentioned in articles and research papers. One example is the marine environment. Although the impacts of the disaster were diverse, marine ecosystems generally showed great resilience, something which may serve as an inspiration to local communities as seen in Minamisanriku town. Other papers say that beds of kelp over shallow rocky reefs appear to have sustained minimal damage, which shows that this species can be surprisingly strong against large disturbances, while mature abalone, which live among kelp forests, were also minimally impacted, and sea urchins bounced back faster. These are strong signs of just how resilient nature can be against large disturbances, while the population sizes of these species immediately after the disaster may have been large enough to ensure the survival of a significant number and perhaps also maintain some genetic diversity.

Another paper published in 2021 describes resilience in the fishing hamlet of Isohama, where buildings and facilities disappeared, fishing boats were destroyed, and surviving fishermen and other community members were moved to surrounding villages and towns. Hiroki Takakura, the paper’s author, discusses the notion of a disaster utopia — temporary collaborative behaviour by those affected by an emergency but which disappears quickly after the emergency has passed — and identifies competitive and cooperative practices among fishermen.

Soon after the disaster, local fishermen were able to participate in a government program to remove debris from the coast and reconstruct fishery infrastructure. Through this, they interacted and exchanged ideas with local residents, and worked together in various ways, such as repairing rope and netting. The fishermen also went out fishing on the few boats that remained, and shared any profits equally among them. Takakura describes how this kind of cooperative practice taps into existing practices of group fishing and the resilient mindset of fishermen. Other papers also draw on the resilience of Japanese people, which is largely attributed to such things as community engagement, and collective understandings of the frequent natural hazards that Japan experiences. This kind of mindset can enable individuals or groups to perhaps better withstand the impacts of large disasters and adapt to changing conditions through preparedness measures, strong community ties and the ability to bound back from setbacks.

In less than two weeks, Japan will be marking the 14th anniversary of the March 11th disaster. While reconstruction has taken a long time, and for many a full recovery will never take place, affected areas are slowly but gradually moving on. Japan suffers from many natural disasters, from earthquakes and tsunamis to strong typhoons. While my interest is primarily in aquaculture and fisheries, myself and many other researchers in this field also want to know about the impacts of natural disasters on the marine environment, how it recovers, and whether aquaculture could contribute to that recovery. I hope that my paper will eventually shed light on this, and how Japan, other countries and their aquaculture sectors could be even better prepared for natural disasters.