At last year’s United Nations Climate Conference COP28, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations unveiled its Global Roadmap for Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG2) without Breaching the 1.5C Threshold. The roadmap identifies 120 actions and key milestones within ten domains, one of which is fisheries and aquaculture.

The FAO describes aquatic food as “a nutritional powerhouse, rich in protein, essential fatty acids, vitamins and vital minerals. It also supports millions, providing incomes and jobs, particularly in coastal regions, bolstering local economies and communities, and should also play an important role in the dietary shift to mitigate emissions.” It is encouraging to see that as we enter a new year, seafood continues to draw attention for many significant reasons.

I’m looking forward to finding out how aquaculture will develop this year, and so too, it seems, is Rabobank, which released its annual seafood production report at the end of 2023. According to the Dutch banking and financial services firm, there are “signs of optimism” ahead, such as a year-on-year shrimp production growth of 4.8 percent in 2024, surpassing 2022’s peak volumes. Global Atlantic salmon production is also expected to grow by 4.3 percent and 3.9 percent respectively in 2024 and 2025, with Norway taking the lead. The Faroe Islands and Australia are other emerging markets to watch in salmon farming.

The report also covers some potential risks from higher temperatures that could lead to more algal blooms and mortalities. My work in 2023 began with a series of articles on this very subject and the efforts of countries such as the US to lessen the negative effects through modelling, forecasting and using sensors that assemble data on ocean conditions, currents, algal species abundance and toxin levels. The risks of algal blooms were also described by the Sustainable Aquaculture Innovation Centre (SAIC) in Scotland as one of aquaculture’s biggest emerging challenges. Hopefully, however, new technological advances will continue to make the sector even better equipped to deal with the risks.

Fish health and welfare could also be in the spotlight. At the end of 2023, I was asked by Hatchery International magazine – which will be celebrating its 25th year anniversary in 2024 — to write a story about aquaculture certification and fish health and welfare standards. This topic is key not only from a public perception standpoint, but also from a productivity standpoint. A fish that is healthier and less stressed will grow better and faster, and organisations like SAIC are taking note of this with new research projects on parasite management, managing or preventing disease through immunisation and vaccinations, gill health in Atlantic salmon and more. Work such as this will make huge differences to the survivability and wellbeing of fish and help seafood producers provide a nutritious protein source, according to Heather Jones, CEO of SAIC. It will also pave the way for a more robust, environmentally-friendly sector.

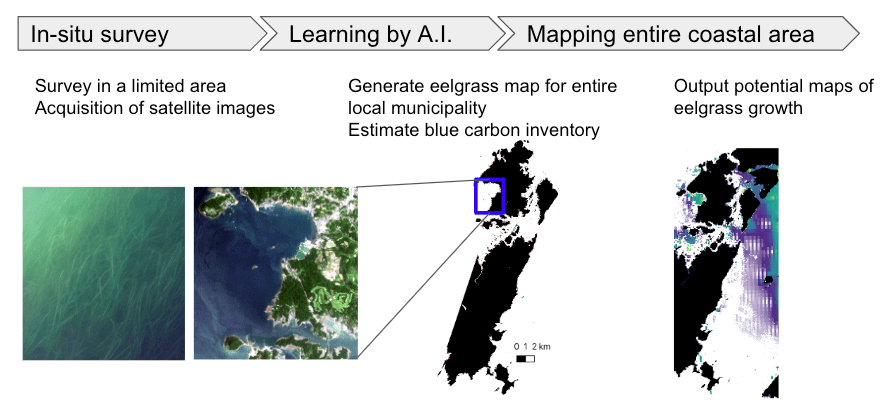

Last year saw significant focus on blue carbon ecosystems as a way of mitigating the effects of global warming. This focus is highly likely to continue in 2024. Blue carbon ecosystems like seagrass and mangroves can capture carbon dioxide through photosynthesis and convert it into biomass. Experts are now saying that restoring these ecosystems is key to removing additional carbon dioxide and addressing other issues such as increasing ocean acidity.

And there’s more. A market is also emerging for carbon credits to finance coastal ecosystem restoration projects. In Japan, the number of such projects, or blue carbon projects, is growing, with major companies keen to purchase credits as a way of not only offsetting their own emissions but also contributing to a local community and fostering regional development. Last year, I started working with consultancy firm Hatch Innovation Services on a blue carbon project with Japanese oil and gas corporation Idemitsu. Studies are underway to explore the potential of these projects in Japan, as seagrass and seaweed become increasingly recognised for their immense promise in addressing climate change and promoting environmental sustainability.

But what does this mean for aquaculture? Many blue carbon projects in Japan focus on seagrass and tidal flats, but there could also be some potential in seaweed, which the Japanese farm extensively and have been consuming for decades. With a strong seaweed sector, Japan is in a unique position and there could be more developments. This month, the country announced that it is recognising seaweed as a carbon sequestering ecosystem and incorporating it into its national carbon emission calculations. This is a hugely significant step, and it feels as though Japan’s current blue carbon projects are the start of a major emerging blue carbon credit market. Success depends on many factors, such as effective engagement with local communities to build trust and transparency, active monitoring and data collection, and a strong presence by companies in the project that they wish to support.

As the Hatch/Idemitsu project continues into 2024, I would love to see other Japanese companies engaging in blue carbon in a similar way. There are still some limitations when it comes to knowledge and information, for example the differing capacities of ecosystems to store carbon, and more communication and research are needed to improve our understanding of blue carbon ecosystems and how they remove carbon dioxide. No doubt, however, big contributions will be made in future to improve the resilience of blue carbon ecosystems and enhance the benefits derived from habitat protection to local communities.

I’m looking forward to seeing how this all develops and the opportunities it will present for those in Japan’s seaweed space.

One of my major goals in 2024 is to write my own research paper as a continuation of my MSc thesis on aquaculture recovery in Tohoku, northeast Japan, after the March 11th, 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster. Over the years, I have found that topics such as disaster risk management and aquaculture/fisheries recovery following natural disasters are not highlighted as frequently as others, and there appear to be much less examples from Japan compared to other countries. My aim is to highlight the particular characteristics of Tohoku’s aquaculture and marine environment, describe the disaster’s impacts and how the sector is working towards recovery, to assess whether Japan’s experience could serve as an example of disaster management and help other countries better understand what happened to aquaculture in Tohoku. I hope that the paper will contribute to formulating plans to reduce the risks and impacts of disasters and steer recovery processes on to the fastest track.

Also coming up this year is the Global Seafood Alliance’s Responsible Seafood Summit 2024, which will be held in St Andrews, Scotland, in October. This event is a great opportunity to network, discover new products and solutions and find out the latest in aquaculture and fisheries research. It’s a huge platform for industry, NGOs, academia and more to share knowledge and information and be part of a varied conference programme covering production, sustainability, innovation, market trends and more. I’m looking forward to learning plenty when I return to St Andrews for the first time since my graduation in 2018.