Seaweed is one of the world’s most sustainable and nutritious crops. It requires neither freshwater nor fertiliser, absorbs dissolved nitrogen, phosphorous and carbon dioxide directly from the sea and proliferates at an impressive rate. The large-scale cultivation of seaweed has been practised in Asia for decades, but more recently it’s become prominent in other parts of the world.

In February, there was a huge focus on seaweed farming in aquaculture circles. The Seagriculture Asia-Pacific Conference was held online early in the month. This two-day event addressed the essentials of scaling seaweed farming, the current status and future development plans for farming seaweed in Vietnam, advancing it in the North Atlantic and Eastern Pacific, new markets for a productive and scalable seaweed industry, seaweed biopackaging and a whole lot more.

Soon after the Seagriculture conference, I met up with Fed de Gobbi, a fellow Bristolian who hosts the podcast Inside Seaweed. Once a month, Fed and his guests talk about seaweed and the benefits of farming it in relation to issues such as climate change. The podcast is also a chance to listen to how his guests became seaweed farmers. Fed and I talked about this and more, including people who might want to set up a seaweed farm, the tools they might need, the problems they could face and the type of help that might be out there. We’ve also had this year’s International Seaweed Symposium in Australia, while my February feature for Global Seafood Alliance also covered seaweed.

Seaweed in the Sea of Japan. Credit: Bonnie Waycott

It’s not hard to see why seaweed is having its moment in the sun. Agriculture’s capacity to meet future food demands is becoming limited because of the reduced availability of arable land and freshwater. Meanwhile, reducing greenhouse gas emissions is a huge challenge, as is habitat degradation on land. With agriculture becoming more untenable, we are being pushed out to sea. Aquaculture has long been seen as a promising way to meet sustainable development goals and feed a growing global population. But how can the sector do this?

One answer to this question is seaweed farming. Seaweed is rich in protein, Vitamin B12 and trace minerals, while iodine and omega-3 fatty acids, which many seaweeds have in abundance, are essential for brain development. It also has potential as animal feed and even beyond food as a packaging replacement for plastics and biofuel. Seaweed farming also offers economic opportunities to coastal communities that have lost jobs due to declining commercial offshore fisheries, while one study shows that seaweed could absorb as much carbon as the Amazon. With all the talk of poor ocean health and predictions of seas without fish, seaweed farming offers hope that there is still a way to work sustainably with the ocean.

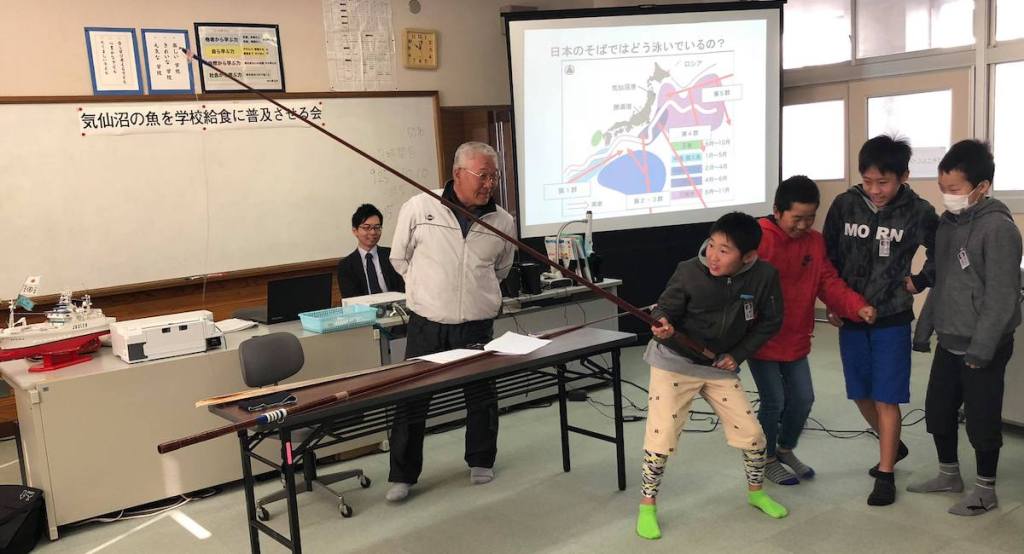

Seaweed farming in Tohoku, Japan. Credit: Hiroshi Sato

Here in the UK, the Pembrokeshire coastline in Wales is home to commercial venture Câr-y-Môr, which means “for the love of the sea” in Welsh. This community-owned business is aiming to become the first commercial seaweed and shellfish farm in Wales and improve the coastal environment and community of the UK’s smallest city St Davids by creating jobs and giving local people a route into the Welsh seafood sector. The farm grows sugar kelp with scallops and oysters, replicating a farming model that was pioneered in the US by Bren Smith, founder of NPO GreenWave that focuses on developing regenerative ocean farming. It uses a polyculture system where a mixture of shellfish and seaweed are grown without freshwater, fertiliser or feed, while capturing and storing carbon. Another example of seaweed farming is Norway’s Seaweed Solutions, which supplies the food industry and other markets with sugar kelp, winged kelp and other species that are farmed off the island of Frøya.

Photo credit: Ben Wicks, Unsplash

If seaweed farming continues to grow, could we see more people eating it? The consumption of seaweed remains somewhat niche in the west and much more common in Asian countries, but despite this, Western countries are starting to embrace seaweed as a food ingredient. Perhaps one of the most famous examples is nori seaweed, which is used in sushi as an edible wrap. But many people are still less familar with seaweed, with first impressions of it less than appealing. It’s often seen as a smelly, salty or slimy plant that washes up on beaches.

One study shows that taste and familiarity have the most influence on participants’ willingness to try and buy seaweed-based foods, with the healthy attributes of seaweed less important. Luckily, seaweed is extremely versatile — it can be added to a range of products to enhance taste, thicken soups, stabilise texture or act as an alternative seasoning to salt. Furthermore, thinking about what we eat has become an important environment-related talking point. With more people eating less meat and dairy, the consumption of plant-based products, plant-based milk like almond, soya and oat milk, and daily alternatives like plant-based yogurt are all on the rise. Seaweed could be a worthy addition to this list. It is suggested that if future seaweed products are to draw attention, taste-focused language on packaging (delicious, rich) and recipe ideas for consumers (how to make a seaweed salad or serve seaweed as a side dish) could be two important marketing strategies.

The current focus on seaweed farming is extremely encouraging and I have no doubt that it will continue. It is often viewed as the pinnacle of sustainable aquaculture but it’s also important to better understand the possibilities it offers and any possible effects, for example on the marine environment. Could seaweed change environmental conditions or become invasive in a new habitat? This type of work will help to enhance our knowledge of seaweed farming and the potential to explore and further develop it. If we can work with seaweed to improve environmental practices and more, we could be one step closer to feeding a growing population and maintaining healthier seas.

Seaweed on longline. Credit: Tom McDermott