Over the past few months, the words regenerative aquaculture have been featuring prominently in aquaculture circles following the release of a new study by The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the world’s leading conservation organisation, and The University of New England. Published in the journal Reviews in Aquaculture, it shows that seaweed and shellfish farming is a critical part of regenerative food production and helps meet the needs of a growing population while working to maintain and improve ocean health.

According to the study, mussel farms appear to be the most beneficial for enhancing the volume of marine life, as 3.6 times more fish and invertebrates seem to appear around those farms compared to others. Oyster farms also help to increase species diversity by providing food, places to forage and reproductive grounds for fish. The study is a great read and a fantastic example of the positive impact that aquaculture can have on our oceans.

Seaweed farming in Tohoku, Japan

Credit: Hiroshi Sato

Farmed scallops in Tohoku, Japan

Credit: Hiroshi Sato

Farmed scallops in Japan

Credit: Hiroshi Sato

Seaweed in Tohoku, Japan

Credit: Hiroshi Sato

But what exactly is regenerative aquaculture? Perhaps the biggest and most well-known example is the work of GreenWave, which uses the term regenerative ocean farming. GreenWave is a US nonprofit that grows shellfish, kelp and other sea vegetables that don’t require any freshwater, fertilisers or feed. Instead, these species soak up nutrients while sequestering carbon and rebuilding ecosystems.

GreenWave’s model involves hanging seaweed, kelp, scallops and mussels from buoys, while cages with oysters and clams lie beneath. Growing a mix of species, each playing a vital role, mimics the diversity of ocean reefs. Kelp can act as a physical cushion in storm surges, absorbing energy from high waves, while seaweed and shellfish provide a safe haven for marine life and a habitat that can foster biodiversity and support the health of an array of species. The setup can also provide jobs to local communities that rely on the sea to make a living. Both seaweed and shellfish also require zero inputs as they utilise sunlight alongside nutrients and plankton that are already in the water to grow. This means that the primary sources of aquaculture pollution – fish feed, chemical fertilisers and other synthetic chemicals – are not part of the equation.

But the ability of shellfish and seaweed to fight the pressing issue of climate change is undoubtedly worth mentioning. Seaweed is incredibly efficient when it comes to taking in carbon for growth and mitigating the impacts of ocean acidification. One study estimates that it could sequester around 173 million metric tonnes of carbon each year. Shellfish, meanwhile, filter nitrogen out of the water column (the main nitrogen polluter is agricultural fertiliser runoff that ends up in the ocean). Nitrogen is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. It’s an essential part of life but too much has a devastating effect on our land and ecosystems.

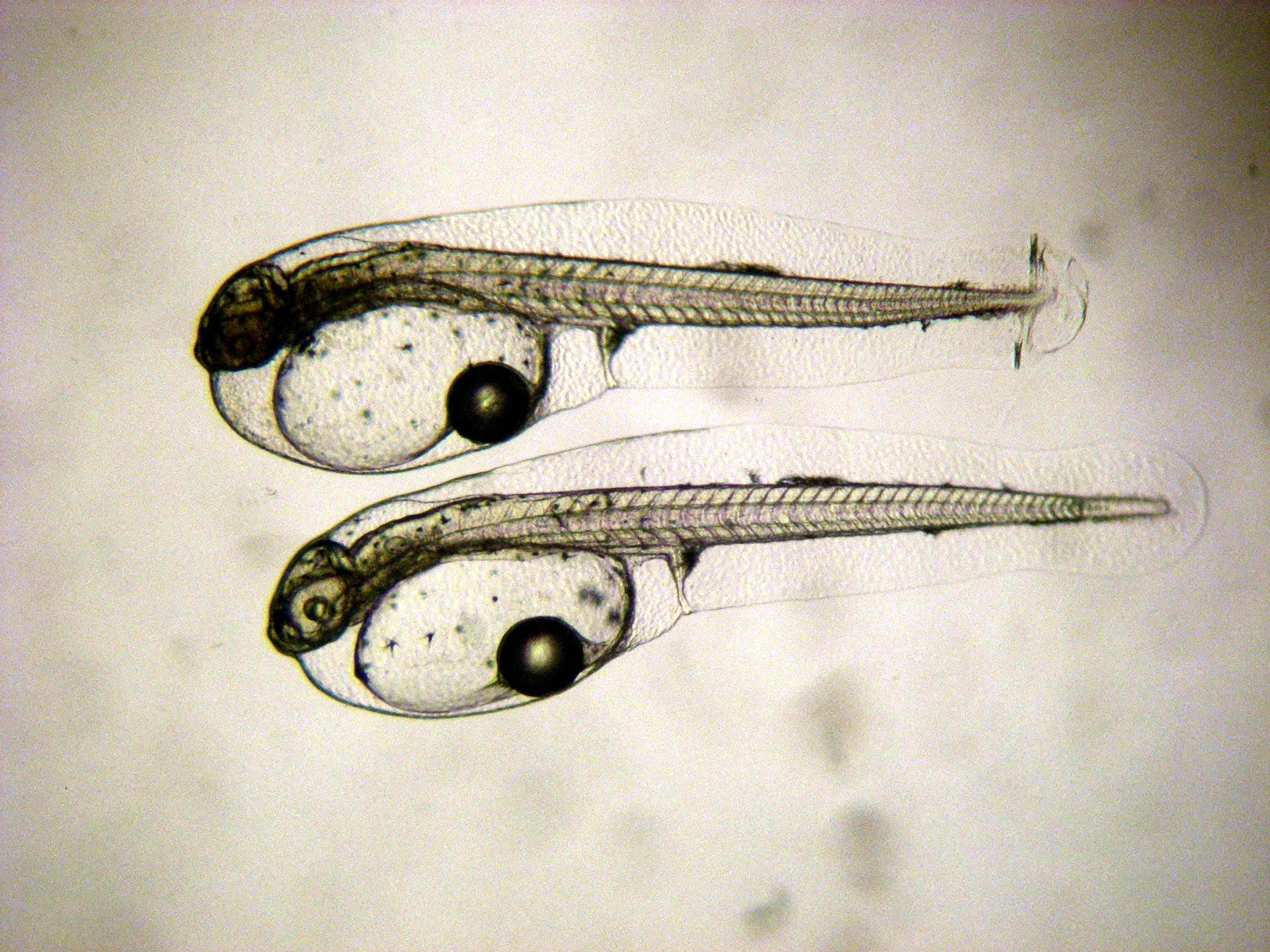

Regenerative aquaculture offers large quantities of food while ocean conditions are improved and greenhouse gases are absorbed. That’s a huge win for us, but it doesn’t stop at humans. Integrating seaweed into fish feed as a fishmeal and fish oil alternative could also have potential, says Dr. Julie Ekasari of Bogor Agricultural University in Indonesia. “Based on its nutritional composition, seaweed is indeed a promising feed raw material,” she told me. “It can contribute to the supply of some essential nutrients and bioactive compounds that further upgrade the function of the feed. From a production point of view, seaweed culture is also relatively inexpensive with simple technology. We believe that the need for seaweed as a marine-based feed raw material will continue to increase in future.”

“Some studies have shown that dietary seaweed supplementation could enhance the levels of some bioactive compounds and essential minerals such as carotenoids and iodine in fish meat. In this sense, we can hypothesise that it may also enhance the health benefits of cultured fish for human consumption,” she continued.

Regenerative aquaculture is drawing attention at the right time. The Nature Conservancy study was released amidst much focus on the negative environmental impacts of food production, so this couldn’t be a better opportunity to highlight aquaculture’s potential. In addition, various organic and sustainability movements over the years have made us think more about how our food is raised, grown, harvested, processed and how it impacts the environment. Meanwhile, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, we’ve become more aware of supply chain disruptions, how far our food has been travelling and the environmental impact of these journeys. Hopes are high that starting with the Nature Conservancy study, the positive impacts of aquaculture will be better recognised and play a key role in the development of an industry that is even better managed and geared towards ecosystem recovery and protection.

Regenerative aquaculture may not be the solution to all the environmental problems out there, but it does show that small steps can have really significant results. As we continue to look closely at our food systems and topics such as climate change become part of everyday conversations, regenerative aquaculture definitely needs to be part of the solution.

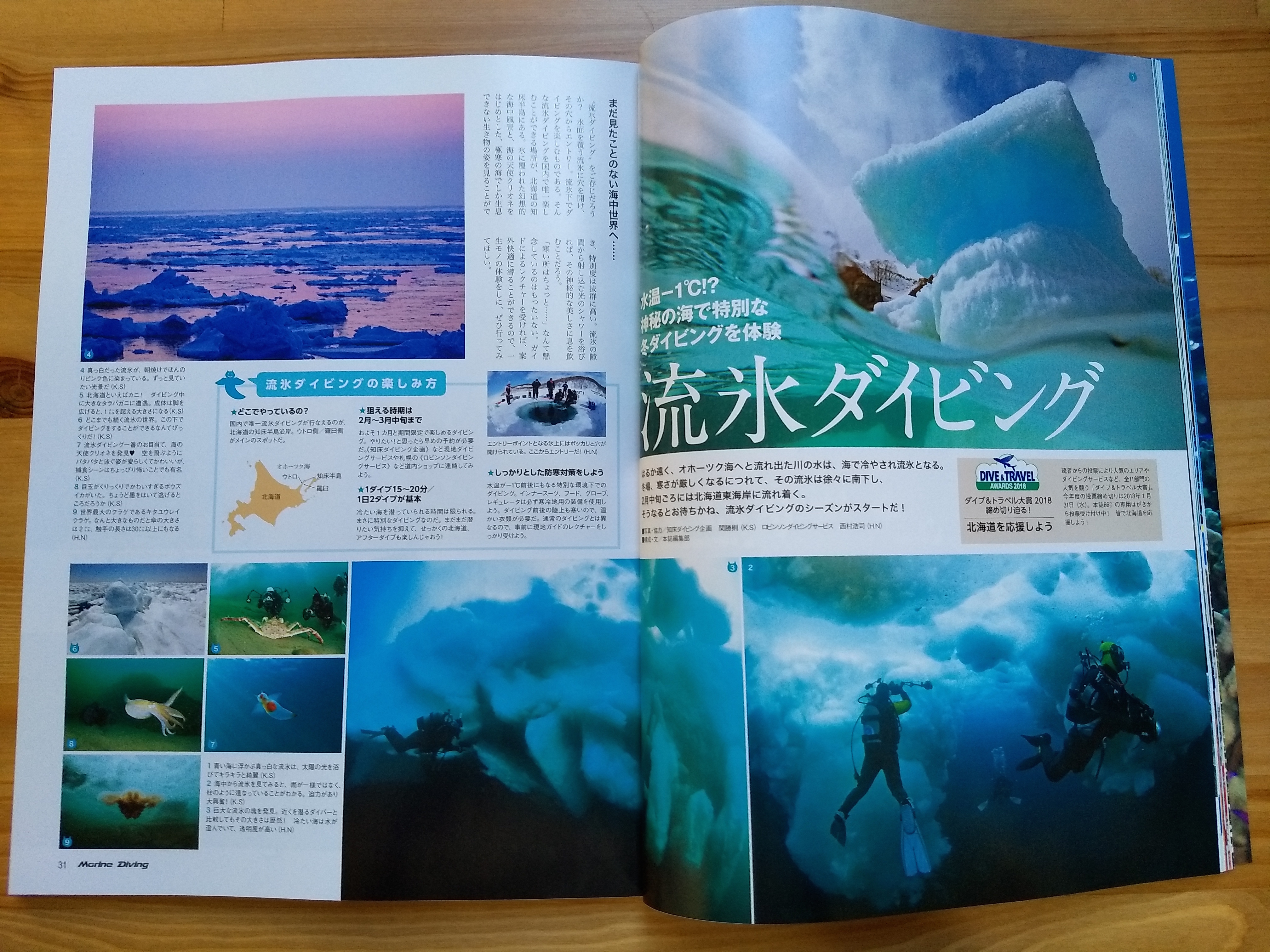

Each winter off the northernmost island of Hokkaido, ice floes from Sibera are blown down across the Sea of Okhotsk, where they settle around the Shiretoko Peninsula, becoming more rounded as their edges soften. It is here that the ice diving season begins, running in February and March. While it’s possible to spot a few fish, most divers come to see the tiny, transparent sea angel or clione. Besides the mesmerising layers of ice on the water surface, ice diving also provides other unique experiences.. Visibility is excellent, while particulate matter settles more easily thanks to the calm sea. The rocky topography is also home to seagrass, crabs, starfish, shrimp and even tiny nudibranchs if you have a keen eye and are brave enough to withstand the -1C temperatures for long enough to keep looking.

Each winter off the northernmost island of Hokkaido, ice floes from Sibera are blown down across the Sea of Okhotsk, where they settle around the Shiretoko Peninsula, becoming more rounded as their edges soften. It is here that the ice diving season begins, running in February and March. While it’s possible to spot a few fish, most divers come to see the tiny, transparent sea angel or clione. Besides the mesmerising layers of ice on the water surface, ice diving also provides other unique experiences.. Visibility is excellent, while particulate matter settles more easily thanks to the calm sea. The rocky topography is also home to seagrass, crabs, starfish, shrimp and even tiny nudibranchs if you have a keen eye and are brave enough to withstand the -1C temperatures for long enough to keep looking.